SAFETEA-LU Section 6009

Implementation Study

Phase I Report — February 2010

|

U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

Office of Project Development and Environmental Review

|

|

U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Transit Administration

Office of Human and Natural Environment

|

Preface/Acknowledgments

This Report to Congress was prepared by a project team comprised of employees of the U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), Federal Transit Administration (FTA), and John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center (Volpe Center). The project team wishes to thank the numerous stakeholders who graciously offered their time, knowledge, and guidance in the development of this implementation study.

List of Figures

List of Tables

abbrs, Abbreviations, and Definitions

Executive Summary

Introduction

Background

Report Purpose

Report Contents

Phase I Evaluation Methodology

SAFETEA-LU Section 6009 Implementation Study Plan

Selection of Projects with De Minimis Impact Determinations

Interview Strategy

Study Data Quality and Research Limitations

De Minimis Impact Determinations Inventory

Study Findings

Efficiencies Resulting From the De Minimis Impact Provisions

Time Implications

Cost Implications

Post-Construction Effectiveness of Impact Mitigation and Avoidance Commitments Associated with the De Minimis Impact Provision

Resource Protection Outcomes

Transportation Project Outcomes

Institutional Considerations

Feasible and Prudent Avoidance Alternatives Standards

SAFETEA-LU Requirements

DOT's Rulemaking Process

Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

Public Comments on the NPRM

Final Rule

Conclusions

Appendix A. Flowcharts of Section 4(f) Process and Section 4(f) De Minimis Impact Determination Process for Historic Properties, Parks, Recreation Areas, and Wildlife and Waterfowl Refuges

Appendix B. SAFETEA-LU Section 6009 Implementation Study Plan

Appendix C. TRB Letter Report

Appendix D. DOT Response to TRB Phase I Letter Report

Appendix E. Interview Selection Strategy and Interview Recommendation

Appendix F. Pre-interview Questionnaire for Transportation Agencies and Interview Guides

List of Figures

| Figure 1 |

Total Reported Projects with De Minimis Impact Determinations by State, FHWA and FTA (as of April 2009) |

| Figure 2 |

Number of De Minimis Impact Determinations per Transportation Project Type (as of April 2009) |

| Figure 3 |

Projects with De Minimis Impact Determinations by Resource Type (as of April 2009) |

| Figure 4 |

Share of De Minimis Impact Determinations by NEPA Class of Action (as of April 2009) |

| Figure 5 |

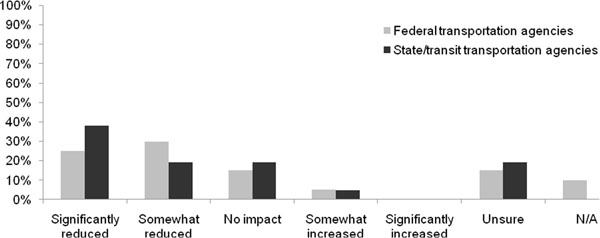

Effect of the De Minimis Impact Provision on the Timeliness of Completing the Section 4(f) Requirements |

| Figure 6 |

Effect of the elimination of the requirement to coordinate with and obtain comments from DOI on the time associated with completing the Section 4(f) process |

| Figure 7 |

Effect of the elimination of the FHWA/FTA legal sufficiency review process on the time associated with completing the Section 4(f) process |

| Figure 8 |

Effect of the elimination of the requirement to design and evaluate alternatives on the time associated with completing the Section 4(f) process |

| Figure 9 |

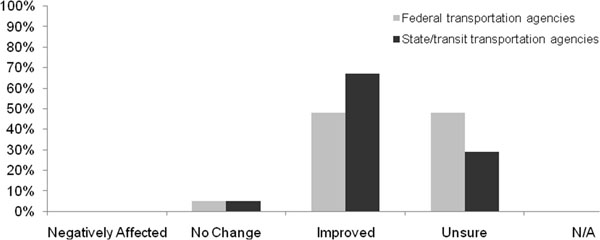

Effect of the addition of the public comment and review requirements (for parks, recreation areas, and refuges) on the time associated with completing the Section 4(f) process |

| Figure 10 |

Effect of being able to rely on a Section 106 determination to reach a Section 4(f) determination (for historic properties) on the time associated with completing the Section 4(f) process |

| Figure 11 |

Effect of the De Minimis Impact Provision on the Cost of Completing the Section 4(f) Requirements |

| Figure 12 |

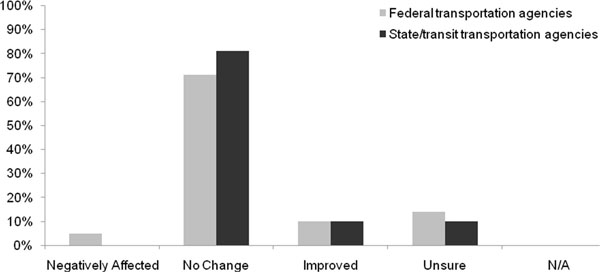

Effect of the De Minimis Impact Provision on Protection of Section 4(f) Resources |

| Figure 13 |

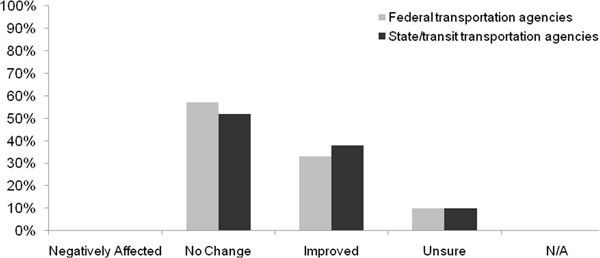

Effect of the De Minimis Impact Provision on Transportation Project Outcomes |

List of Tables

| Table 1 |

Comparison of De Minimis Impact Inventory (as of March 21, 2008) — Population, Original Interview Sample, and Final Interview Sample |

| Table 2 |

Characteristics of Projects Studied |

| Table 3 |

Class of Action, Cost, and Size of Projects with De Minimis Use Impact Determinations by Property Type (as of April 2009) |

| Table 4 |

De Minimis Impact Determinations by Highway Project Type |

abbrs, Abbreviations, and Definitions

| AASHTO |

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: A nonprofit, nonpartisan association representing highway and transportation departments in the 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. |

| ACHP |

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation: An independent Federal agency that promotes the preservation, enhancement, and productive use of our Nation's historic resources, and advises the President and Congress on national historic preservation policy. |

| CE |

Categorical Exclusion: A category of actions which do not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the human environment. |

| CFR |

Code of Federal Regulations: The codification of the general and permanent rules published in the Federal Register by the executive departments and agencies of the Federal Government. |

| DOI |

U.S. Department of the Interior |

| DOT |

U.S. Department of Transportation |

| EA |

Environmental Assessment: Under NEPA, when the significance of impacts of a transportation project proposal is uncertain, an EA is prepared to assist in making this determination. |

| EIS |

Environmental Impact Statement: NEPA requires Federal agencies to prepare EISs for major Federal actions that significantly affect the quality of the human environment. An EIS is a full disclosure document that details the process through which a transportation project was developed, includes consideration of a range of reasonable alternatives, analyzes the potential impacts resulting from the alternatives, and demonstrates compliance with other applicable environmental laws and executive orders. |

| FHWA |

Federal Highway Administration |

| FR |

Federal Register: The official daily publication of rules, proposed rules, and notices of Federal agencies and organizations, as well as executive orders and other presidential documents. |

| FRA |

Federal Railroad Administration |

| FTA |

Federal Transit Administration |

| HUD |

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development |

| NCSHPO |

National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers: A professional association of the State government officials who carry out the national historic preservation program as delegates of the Secretary of the Interior. |

| NEPA |

National Environmental Policy Act: Signed into law in 1970, NEPA established a supplemental mandate for Federal agencies to consider the potential environmental consequences of their proposals, document the analysis, and make this information available to the public for comment prior to implementation. |

| NPRM |

Notice of Proposed Rulemaking: Notice that precedes the issuance of a final rule, which is an agency process for formulating, amending or repealing a rule. |

| Overton Park |

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe: A decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that established the basic legal standard for compliance with Section 4(f). |

| PA |

Programmatic Agreement: A document that spells out the terms of a formal, legally binding agreement between a State department of transportation (DOT) and other State and/or Federal agencies. |

| SAFETEA-LU |

Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users: The statute that authorizes the Federal surface transportation programs for highways, highway safety, and transit for the 5-year period 2005-2009.

|

| SCOE |

AASHTO Standing Committee on the Environment |

| Section 4(f) |

49 U.S.C. § 303 and 23 U.S.C. 138: This statute protects public parks, recreational areas, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, and public and private historical sites from use by proposed transportation projects unless (1) There is not feasible and prudent alternative to the use of such land and the action includes all possible planning to minimize harm to the property resulting from the use, or (2) The use is determined to have a de minimis impact on the property. |

| Section 106 |

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, Section 106, requires Federal agencies to take into account the effects that their federally funded activities and programs have on significant historic properties. 16 U.S.C. § 470(f) |

| Section 6009 |

SAFETEA-LU Section 6009 Parks, Recreation Areas, Wildlife and Waterfowl Refuges and Historic Sites: This statute section made the first substantive revision to Section 4(f) since the Department of Transportation Act of 1966. 49 U.S.C. § 303; 23 U.S.C. § 138 |

| SHPO |

State Historic Preservation Officer: This person administers the national historic preservation program at the State level, including Section 106. |

| THPO |

Tribal Historic Preservation Officer: This person assumes the responsibilities of the SHPO for purposes of Section 106 compliance on tribal lands. |

| TRB |

Transportation Research Board: This board is one of six major divisions of the National Research Council. |

| USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

| DOT |

U.S. Department of Transportation |

Executive Summary

This document, Phase I Report — February 2010 (Phase I), presents findings from the first of two study phases to assess the implementation of Section 6009 of the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU). Section 6009(c) requires the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) to conduct a study and issue a report no sooner than August 10, 2008, on the implementation of the amendments made by SAFETEA-LU to Section 303 of title 49 and Section 138 of title 23, commonly referred to as Section 4(f) from the Department of Transportation Act of 1966. Section 4(f) protects publicly owned parks, recreational areas, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, and public and private historical sites from use by transportation projects unless DOT determines that there is no feasible and prudent avoidance alternative and that all possible planning to minimize harm has occurred.

Section 6009 of SAFETEA-LU amended Section 4(f) to: (1) clarify the factors considered and the standards applied in determining the prudence and feasibility of alternatives that avoid uses of Section 4(f) properties; and (2) provide a simplified approval process of projects that have de minimis impacts on Section 4(f) property. De minimis impact, in general terms, means that the use of the transportation project will not adversely affect the activities, features, and attributes of the Section 4(f) property.

Phase I evaluates how the de minimis impact provision has been applied nationwide since it was enacted by SAFETEA-LU in August 2005. It also reviews the implementation process that DOT used to clarify the factors to consider and standards to apply for determining the “prudence and feasibility” of alternatives to avoid the use of a Section 4(f) property. A second phase of the study will provide an update to the de minimis impact provision evaluation here as well as an assessment of the application of the new prudent and feasible standards.

The Phase I Section 6009 implementation study findings, which are based on in-depth, qualitative information from a select group of stakeholders, support the perception that the de minimis impact provision can streamline the Section 4(f) process for projects while maintaining protection of those resources. Although the preliminary data do not yet support efficiency gains, some of the officials with jurisdiction over Section 4(f) properties interviewed reported benefits from the transportation agencies’ motivation to protect the resource knowing that a de minimis impact determination could mean a streamlined transportation project. Transportation agencies participating in the study have found that use of the de minimis provision increased their coordination with stakeholders. The result is that the agencies have learned more about the activities, features, and/or attributes of the Section 4(f) resources, which has provided an incentive for them to design projects sensitive to those elements in order to make a de minimis impact determination.

The Phase I evaluation results suggest that the de minimis impact provision can enable transportation agencies to better balance the delivery of transportation projects with protection of publicly owned parks, recreation areas, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, and public and private historical sites. In addition, for the sample analyzed, the de minimis impact provision has simplified the fulfillment of Section 4(f) requirements, particularly in cases where the official with Section 4(f) jurisdiction initiates or sponsors the transportation project.

Phase I interviews and supplementary surveys were used to identify the effectiveness and efficiencies resulting from implementation of the Section 6009 amendments. This approach complies with the requirement in SAFETEA-LU Section 6009 to report this assessment 3 years after the date of enactment of the Act and again by March 1, 2010. Based upon these surveys and interviews and the sample of projects analyzed, DOT concludes the following:

Efficiency Resulting from the De Minimis Impact Provision

- The de minimis impact provision has predominately improved transportation agencies’ timeliness in fulfilling Section 4(f) requirements. A majority (79 percent) of the 42 surveyed transportation officials reported that the de minimis impact provision has reduced the amount of time necessary to complete the Section 4(f) process.

- The officials with Section 4(f) jurisdiction who were interviewed, including State Historic Preservation Officers’ staff (SHPOs) and park, recreation, and wildlife and waterfowl refuge officials, all reported that the de minimis impact provision has not changed the time associated with fulfilling the Section 4(f) requirements as compared to other Section 4(f) processing options.

- The transportation agencies’ interviewed indicated that the de minimis impact provision's elimination of the requirement to design and evaluate avoidance alternatives has generally reduced the time necessary to complete the Section 4(f) process. Forty-five percent of transportation agencies reported that the elimination of the requirement to design and evaluate Section 4(f) resource avoidance alternatives has significantly reduced the time to complete the Section 4(f) process, while 36 percent reported that it somewhat reduced completion time.

- Fifty-seven percent of the surveyed transportation officials reported that the de minimis impact provision has decreased the cost of completing the Section 4(f) process. No respondents reported that costs have increased as a result of the de minimis impact process.

Post-Construction Effectiveness of Impact Mitigation and Avoidance Commitments Associated with the De Minimis Impact Provision

- According to the majority of transportation officials surveyed, the de minimis impact provision has maintained protection of Section 4(f) resources as compared to alternative Section 4(f) processing options (i.e. individual Section 4(f) evaluations and programmatic Section 4(f) evaluations). Most (76 percent) reported that the de minimis provision has had no reduction in the protection of the Section 4(f) resource. Ten percent indicated that it has improved resource protection.

- Four of 10 SHPOs reported that the de minimis impact provision has enhanced consultation and coordination between them and the transportation agency to minimize impacts to Section 4(f) properties. According to these four SHPOs, the de minimis impact provision is another “tool in the toolbox” to encourage transportation agencies to design projects that have fewer adverse impacts to resources.

- None of the five officials with jurisdiction over parks, recreational areas, and wildlife and waterfowl refuges that were interviewed have found that the de minimis impact provision reduces the protection of Section 4(f) resources as compared to other Section 4(f) processing options.

- Officials with Section 4(f) jurisdiction generally have benefited from the transportation agencies‘ motivation to protect the Section 4(f) resource, knowing that a de minimis impact determination could mean a streamlined transportation project. Also, park and recreation officials might have benefitted from an increased involvement in the Section 4(f) process. Because the de minimis impact provision has encouraged improved coordination, transportation agencies have learned more about the activities, features, and/or attributes of park resources. Some transportation agencies reported that this provision is an incentive to design projects sensitive to those elements in order to make a de minimis impact determination.

- Fifty-five percent of the transportation agencies surveyed reported that the de minimis impact provision has not changed the transportation project outcomes. Most projects where the de minimis impact provision was applicable had such minor impacts to the Section 4(f) resources that additional minimization or mitigation efforts, or project design changes, were not required to make the determination. Thirty-six percent of transportation officials noted that project design typically did not change as a result of the de minimis impact provision, but that the process enabled the Section 4(f) process to be completed more quickly and at a reduced cost.

- A few transportation-agency staff and officials with jurisdiction indicated that the de minimis impact provision provides a common sense approach to fulfilling Section 4(f) requirements for projects that clearly have no adverse effect on Section 4(f) resources.

Introduction

Background

Established in the Department of Transportation Act of 1966, Section 4(f) protects publicly owned parks, recreational areas, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, and public and private historical sites from use by transportation projects unless the DOT determines that there is no feasible and prudent avoidance alternative and that all possible planning to minimize harm has occurred. In 2005, amendments were made to Section 4(f) law to: (1) clarify the factors considered and the standards applied in determining the prudence and feasibility of alternatives that avoid uses of Section 4(f) properties; and (2) provide a simplified approval process of projects that have de minimis impacts on Section 4(f) property.

When a project proposes to use resources protected by Section 4(f), a Section 4(f) evaluation must be prepared. There are three options for processing proposed uses of Section 4(f) property: (1) individual Section 4(f) evaluations, (2) programmatic Section 4(f) evaluations, or (3) a determination of de minimis impact.

An individual Section 4(f) evaluation must identify and evaluate alternatives, both location and design shifts that entirely avoid the Section 4(f) resource, and if unavoidable, analyze all possible measures that are available to minimize the proposed action's impacts on the Section 4(f) resource. As part of the individual Section 4(f) evaluation, coordination with the public official having jurisdiction over the Section 4(f) resource and with the Department of the Interior (DOI) is required, and with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), as appropriate. Then, for highway and transit projects, an FHWA or Federal Transit Administration (FTA) lawyer reviews the individual evaluation for legal sufficiency.

Programmatic Section 4(f) evaluations may be used in place of individual evaluations if specific conditions are met. Under a programmatic Section 4(f) evaluation, certain conditions are applied such that, if a project meets the conditions, it will satisfy the requirements of Section 4(f) that there is no feasible and prudent alternative and that the project includes all possible planning to minimize harm. These conditions generally relate to the type of project, the severity of impacts to 4(f) property, the evaluation of alternatives, the establishment of a procedure for minimizing harm to the 4(f) resource, adequate coordination with appropriate entities, and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) class of action.

Programmatic Section 4(f) evaluations simplify the documentation, interagency coordination, and approval processes required to complete a Section 4(f) evaluation. An analysis of avoidance alternatives is still required; however, interagency coordination is only required with the official(s) with jurisdiction and not with DOI, USDA, or HUD for this Section 4(f) evaluation process.

Currently, five programmatic evaluations have been approved for use nationwide for highway projects (Note: existing Section 4(f) programmatic evaluations are specific to FHWA). Programmatic evaluations may be used for:

- Independent walkway and bikeways construction projects

- Historic bridges

- Minor involvements with historic sites

- Minor involvements with parks, recreation areas, and wildlife and waterfowl refuges

- Net benefits to a Section 4(f) property

As noted above, in 2005, SAFETEA-LU made the first substantive revisions to Section 4(f) since the passage of the Department of Transportation Act of 1966. Specifically, SAFETEA-LU Section 6009 Parks, Recreation Areas, Wildlife and Waterfowl Refuges, and Historic Sites (Section 6009) part (a) modified existing law at 23 U.S.C. 138 and 49 U.S.C. 303 to provide a simplified approval process of projects that have de minimis impacts on Section 4(f) property.

De minimis impact, in general terms, means that the use of the transportation project will not adversely affect the activities, features, and attributes of the Section 4(f) property. The de minimis impact criteria and associated determination requirements differ between (1) historic sites and (2) parks, recreation areas, and wildlife and waterfowl refuges.

A determination of de minimis impact on a historic property may be made when all three of the following criteria are satisfied:

- The process required by Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) results in the determination of “no adverse effect” or “no historic properties affected” with the concurrence of the SHPO and/or Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (THPO), and Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) if participating in the Section 106 consultation.

- The SHPO and/or THPO, and ACHP if participating in the Section 106 consultation, is informed of DOT's intent to make a de minimis impact determination based on their written concurrence in the Section 106 determination.

- DOT has considered the views of any consulting parties participating in the Section 106 consultation.

A determination of de minimis impact on parks, recreation areas, and wildlife and waterfowl refuges, may be made when all three of the following criteria are satisfied:

- The transportation use of the Section 4(f) resource, together with any impact avoidance, minimization, and mitigation or enhancement measures incorporated into the project, does not adversely affect the activities, features, and attributes that qualify the resource for protection under Section 4(f).

- The official(s) with jurisdiction over the Section 4(f) property are informed of DOT's intent to make the de minimis impact determination based on their written concurrence that the project will not adversely affect the activities, features, and attributes that qualify the property for protection under Section 4(f).

- The public has been afforded an opportunity to review and comment on the effects of the project on the protected activities, features, and attributes of the Section 4(f) resource.

Unlike programmatic and individual Section 4(f) evaluations, when a de minimis impact determination is made an analysis of avoidance alternatives is not required. Appendix A provides flowcharts comparing the Section 4(f) evaluation process and the de minimis impact determination process for historic properties, parks, recreation areas, and wildlife and waterfowl refuges.

Section 6009(b) of SAFETEA-LU required DOT to promulgate regulations to clarify the factors to be considered and the standards to be applied in determining the prudence and feasibility of alternatives that avoid uses of Section 4(f) properties. The FHWA and FTA published a final rule1 on March 12, 2008, and the new regulation became effective on April 11, 2008.

Section 6009(c) of SAFETEA-LU required DOT to conduct a study and issue a report (herein referred to as the Phase I report) no sooner than August 10, 2008, on the implementation of the new Section 4(f) provisions and requirements. Specifically, SAFETEA-LU stipulated that the following should be evaluated:

- The new processes developed under Section 6009 and the efficiencies that may result.

- The post-construction effectiveness of impact mitigation and avoidance commitments adopted as part of projects conducted under Section 6009.

- The number of projects with impacts that are considered de minimis, including information on the location, size, and cost of the projects.

Section 6009(c) also requires DOT to submit an update to the report (Phase II) to Congress.

Report Purpose

The primary purpose of this report is to provide Congress, DOI, and the ACHP an evaluation of:

- The processes developed under Section 6009, the new de minimis impact provision and the efficiencies that may result.

- The post-construction effectiveness of impact mitigation and avoidance commitments adopted as part of projects that have relied upon the provisions of Section 6009.

- The quantity of projects with impacts that are considered de minimis, including information on the location, size, and cost of the projects.

The Phase I report also reviews the process DOT used to clarify the factors to consider and standards to apply for determining the “prudence and feasibility” of alternatives to avoid the use of a Section 4(f) property. This report is not intended to serve as a legal review of Section 6009 compliance. This Phase I report fulfills, in part, the requirement for the Secretary to report not earlier than 3 years from the date of enactment of the Act (August 10, 2005, through August 10, 2008) on the results of an evaluation study. The balance of this obligation will be fulfilled with the completion of Phase II of this study, due March 1, 2010. To benefit from the completion of the Phase I report and allow at least a year of implementation time for evaluation between the first and second phase of the study, the Phase II report will be fulfilled later than March 1, 2010.

During the Phase I study effort, DOT determined that sufficient information would not be available by August 2008 to adequately evaluate the implications of the new prudent and feasible standards. Phase II will evaluate the implementation efficiencies and effectiveness of the final rule on the prudent and feasible standards issued on March 12, 2008. The Phase II study and report will also update information on the implementation of de minimis impact determinations.

Report Contents

This Phase I report consists of five primary sections.

“Phase I Evaluation Methodology” describes how DOT selected a representative sample of projects from across the country to conduct surveys, interviews and analysis. The section explains the rationale for using the approach and identifies the constraints of the approach.

“De Minimis Impact Determinations Inventory” provides information on projects with impacts that are considered de minimis, including information on projects’ location, type, and cost.

“Study Findings” presents the initial results from the implementation of the de minimis impact provision. This section covers three areas: (1) Efficiencies resulting from the de minimis impact provisions, including findings on the time and cost impacts of utilizing the de minimis impact provision; (2) Post-construction effectiveness of impact mitigation and avoidance commitments associated with the de minimis impact determinations, which includes findings on the outcomes of the impacts on Section 4(f) resources and transportation project outcomes; and (3) Institutional factors associated with implementation of the de minimis impact provision.

“Feasible and Prudent Avoidance Alternatives Standards” documents the rulemaking process FHWA and FTA undertook to issue the new Section 4(f) regulation.

“Conclusions” summarizes the findings from the Phase I study.

The appendices consist of the: A) Section 4(f) process flowcharts; B) SAFETEA-LU Section 6009 study implementation plan (including SAFETEA-LU Section 6009 text); C) Transportation Research Board's (TRB) letter report comments on the study implementation plan (dated June 9, 2008); D) response to TRB's letter report (dated April 7, 2009) on the draft Phase I study; E) method for selecting projects to evaluate in the study; and F) the pre-interview questionnaire and guides used to focus interviews conducted.

Phase I Evaluation Methodology

SAFETEA-LU Section 6009 Implementation Study Plan

On March 31, 2008, DOT delivered a draft implementation study plan describing the proposed methodology for conducting the Section 6009 evaluation to TRB, as directed by Congress [SAFETEA-LU Section 6009(c)(1)(B)]. The draft study plan for the evaluation of the de minimis impact provision described a largely qualitative approach for selecting and interviewing a sampling of transportation projects for further examination (Appendix B). The draft study plan also included proposed questions designed to elicit information on the perception of any efficiencies resulting from the de minimis impact provision and to learn about the effectiveness of post-construction mitigation and avoidance commitments implemented as a part of the de minimis impact provision. The questions, which would be asked in a series of stakeholder telephone interviews, would form the empirical basis of the required evaluation. In addition, the draft study plan described a review of the process the DOT used to clarify the feasible and prudent standards. The review included:

- Documenting the rulemaking process used to develop the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM).

- Analyzing the rationale and methods used for making the changes to the Section 4(f) regulation outlined in the NPRM.

- Documenting changes made in the final rule.

On June 24, 2008, TRB submitted a letter report to DOT of their independent review of the proposed study plan. The TRB suggested several ways to strengthen the study plan, offering conceptual suggestions for how to structure an approach to data collection and analysis (Appendix C). DOT responses to these recommendations are below and attached (Appendix D).

One suggestion for a quantitative study approach was an ex post facto design with nonequivalent control, which involves the comparison of data regarding the duration, costs, and outcomes associated with two comparable sets of Section 4(f) evaluations — one set being de minimis impact determinations and the other pre-amendment projects where the characteristics of the project suggest that a de minimis impact determination would have been applied. Upon review of existing data from sources including FHWA and DOI, DOT determined that sufficient data were not available to compare de minimis impact determinations with pre-SAFETEA-LU projects. As discussed in more detail below, States have not historically collected data regarding project details and the time and costs associated with the Section 4(f) process.

The DOI maintains a Section 4(f) database for all individual Section 4(f) evaluations that the DOI reviews. Information captured includes the date DOI received the Section 4(f) evaluation, the NEPA class of action, the date the DOI reviewed the evaluation, and a summary of DOI's comments. The DOI data do not include information on the Section 4(f) related time, cost or outcomes, nor does DOI collect information regarding programmatic Section 4(f) evaluations. Thus, DOT determined that the DOI data did not provide a means to compare de minimis impact determinations with pre-amendment projects.

Because of the lack of pre-amendment data, the study team relied upon a scenario-based approach to analyze the effects of the de minimis impact provision. The DOT identified a set of projects where de minimis impact determinations were made and, through interviews with project stakeholders, asked questions regarding how the Section 4(f) evaluation would have been carried out in the absence of the de minimis impact provision (Appendix E and F). At the time of the Phase I analysis, no other DOT mode, namely the Federal Railroad Administration or the Federal Aviation Administration, had made a de minimis impact determination. Therefore, Phase I focused exclusively on FHWA and FTA.

Selection of Projects with De Minimis Impact Determinations

Since 2005, FHWA and FTA have collected information from their division and regional offices on projects that have had de minimis impact determinations.2 The information, which is requested quarterly, includes information on project cost and size, class of action, type of Section 4(f) resources impacted, nature of the de minimis impact determination and any associated mitigation, date of the Section 4(f) de minimis impact determination and the construction start and end dates. At the time the study sample was selected, the March 21, 2008, version of the inventory represented the most-up-to-date information on FHWA and FTA de minimis impact determinations. Data on de minimis impact determinations that were collected after this date were not used to determine the study sample.

As of March 21, 2008, 636 de minimis impact determinations were made for 245 projects in 41 of 52 FHWA Federal-aid Division Offices, 2 of 3 Federal Lands Highway Division Offices3 and 3 of the 10 FTA regions. Records in the de minimis impact inventory indicated that of the 245 projects, 23 had completed the construction phase. With input from TRB and its letter report, DOT designed its selection criteria to ensure that a diverse group of Section 4(f) de minimis impact projects was examined, and that a stratified and representative set of stakeholders was identified for the evaluation.4 To date, the majority of de minimis impact determinations have involved highway projects rather than transit projects, projects classified as Catagorical Exclusions (CEs) rather than ones classified as Environmental Assessments (EAs) or Environmental Impact Statements (EISs), and historic properties rather than parks, recreational areas, or wildlife and waterfowl refuges. Selecting a criterion sample ensured that the study evaluated the impacts that the de minimis impact provision has had or may have on a variety of transportation projects, classes of action, and resource types.

The following characteristics of the project population were used as selection criteria:

- Number of States (including the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) within the following de minimis impact determination categories: (1) States that have had 0 projects with a de minimis impact determination; (2) States that have had 1-10 projects with de minimis impact determinations; (3) States that have had 11-15 projects with de minimis impact determinations; and (4) States that have had more than 15 projects with de minimis impact determinations.5

- Mode of project: either highway or transit, with de minimis impact determination.

- Project type: bridge, intersection/interchange, safety, transportation enhancement, widening, or other.

- NEPA class of action: CE, EA, or EIS.

- Type of Section 4(f) resource involved: historic property, park, recreation area, and/or wildlife and waterfowl refuge.

- Federal Circuit Court District in which the project is located (court opinions on Section 4(f) issues have varied): 12 geographic based Court Districts, numbered 1 through 11 plus the District of Columbia

In order to address the requirement to evaluate the post-construction effectiveness of impact mitigation and avoidance commitments, the DOT determined that all 23 projects constructed as of March 21, 2008, should be included in the sample. This approach was intended to avoid reporting on projects‘ expected outcomes, and instead, to capture actual results. The distribution of the subset of 23 constructed projects (hereafter referred to as the “original sample”) across the selection criteria listed above were compared against the distribution of the total population of de minimis projects across each of the selection criteria. On its own, the original sample fell short of providing a sample that was representative of the population of projects. The underrepresented characteristics within the selection criteria were:

- Number of de minimis determinations: 1-10

- Number of de minimis determinations: > 15

- Type of Section 4(f) resource: Historic property

- Type of Section 4(f) resource: Park

- Transportation Project Type: widening

- Transportation Project Type: transit

- Class of Action: EA

- Class of Action: EIS

- Federal Circuit Court District: District of Columbia, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11

In order to address this issue and to ensure that the sample would not be overrepresented by any one type of project, three additional projects were added to the study sample. These three projects were chosen based on the number of criteria that these projects satisfied. The following projects, which satisfied the most criteria, were selected:

- Additional project number one: 1-10 de minimis determinations, EA, park, transit, Federal Circuit Court District 9

- Additional project number two: Greater than 15 de minimis determinations, EA, historic resource, widening, Federal Circuit Court District 11

- Additional project number three: 1-10 de minimis determinations, EIS, park, widening, Federal Circuit Court District 10

Table 1 illustrates the characteristics that where underrepresented in the preliminary sample (see gray shading) and how they were addressed.

Table 1. Comparison of the De Minimis Impact Inventory Population, Original Interview Sample, and Final Interview Sample

| |

Projects in Inventory as

of March 21, 2008 |

Construction Completed

Original Sample |

Final Sample |

| Number of de minimis findings |

State Count |

|

Sample Count |

|

Sample Count |

|

| 0 |

11 |

21% |

— |

— |

3 |

10% |

| 1 — 10 |

32 |

62% |

11 |

48% |

13 |

45% |

| 11 — 15 |

4 |

8% |

4 |

17% |

4 |

14% |

| > 15 |

5 |

10% |

8 |

35% |

9 |

31% |

| |

52 |

100% |

23 |

100% |

29** |

100% |

| Type of 4(f) Resource |

Project Count |

|

Sample Count |

|

Sample Count |

|

| Historic Property |

158 |

64.5% |

17 |

74% |

18 |

69% |

| Park |

50 |

20.4% |

4 |

17% |

6 |

22% |

| Recreation Area |

15 |

6.1% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| Wildlife Refuge |

3 |

1.2% |

1 |

4% |

1 |

4% |

| Historic Property and Park |

6 |

2.4% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| Historic Property and Rec. Area |

3 |

1.2% |

1 |

4% |

1 |

4% |

| Park and Rec. Area |

3 |

1.2% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| Unknown |

7 |

2.9% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| |

245 |

100.00% |

23 |

100% |

26 |

100% |

| Transportation Project Type |

Project Count |

|

Sample Count |

|

Sample Count |

|

| Highway: Other |

40 |

16% |

7 |

30% |

7 |

27% |

| Highway: Safety |

16 |

7% |

2 |

9% |

2 |

8% |

| Highway: Interchange |

35 |

14% |

4 |

17% |

4 |

15% |

| Highway: Transportation Enhancement |

14 |

6% |

2 |

9% |

2 |

8% |

| Highway: Widening |

55 |

22% |

3 |

13% |

5 |

19% |

| Highway: New Alignment |

17 |

7% |

3 |

13% |

3 |

12% |

| Highway: Bridge |

46 |

19% |

2 |

9% |

2 |

8% |

| Highway: Unknown |

14 |

6% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| Transit |

8 |

3% |

— |

— |

1 |

4% |

| |

245 |

100.00% |

23 |

100% |

26 |

100% |

| Class of Action |

Project Count |

|

Sample Count |

|

Sample Count |

|

| Categorical Exclusion |

186 |

81% |

21 |

91% |

21 |

81% |

| Environmental Assessment |

39 |

17% |

2 |

9% |

4 |

15% |

| Environmental Impact Statement |

4 |

2% |

— |

— |

1 |

4% |

| Re-evaluation |

4 |

2% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| Unknown |

12 |

5% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

| |

229 |

100.00% |

23 |

100% |

26 |

100% |

| Federal Circuit Court District |

Project Count |

|

Sample Count |

|

Sample Count |

|

| District 1 |

21 |

9% |

5 |

22% |

5 |

17% |

| District 2 |

17 |

7% |

1 |

4% |

1 |

3% |

| District 3 |

14 |

6% |

— |

— |

1 |

3% |

| District 4 |

30 |

12% |

2 |

9% |

2 |

7% |

| District 5 |

23 |

9% |

3 |

13% |

3 |

10% |

| District 6 |

19 |

8% |

2 |

9% |

2 |

7% |

| District 7 |

5 |

2% |

— |

— |

1 |

3% |

| District 8 |

11 |

4% |

2 |

9% |

3 |

10% |

| District 9 |

41 |

17% |

4 |

17% |

5 |

17% |

| District 10 |

43 |

18% |

4 |

17% |

5 |

17% |

| District 11 |

21 |

9% |

— |

— |

1 |

3% |

| |

245 |

100.00% |

23 |

100% |

29** |

100% |

*Re-evaluations and projects with an unknown NEPA class of action were not included in the tally.

**The sample count 29 includes 3 States with no de minimis impact determinations and, thus, there is no data for those states in the final sample's transportation project type, class of action, or type of 4(f) resource rows. Note: No projects involving recreation areas only, historic and park properties, or park properties and recreation areas were included in the final sample because no projects involving these resource categories had completed construction. Also, “Unknown” values represent project information for which data was not provided in the inventory.

Based on this strategy, a total of 25 projects from 20 States were selected for inclusion in the final sample for evaluation.6 Although they were chosen based on particular projects’ characteristics, the States that were selected accounted for 222 of the 366 projects (60.6 percent) for which de minimis impact determinations were made and, thus, accounted for a majority of the total experience implementing the de minimis impact provision. During the interview process, DOT found 2 instances where there were discrepancies between data reported in the inventory and the actual number of de minimis impact determinations. The inventory had recorded that for 2 of the initial 20 States in the sample no de minimis impact determinations had been made. However, it was discovered that these States had, in fact, been developing projects in which de minimis impact determinations had been made prior to March 21, 2008. Subsequently, these States were not included in the evaluation because they no longer met the criteria for which they were selected. To fill this gap, an additional State with no de minimis impact determination was identified, and the appropriate representatives were interviewed.

Table 2 below provides information on projects included in the study sample.

Table 2. Characteristics of Projects Studied**

| Project |

State |

NEPA Class

of Action |

Resource Type |

Project Type* |

Cost

(in millions $) |

De MinimisUse Size

(acres)^ |

| 1 |

AK |

EA |

Park |

O |

19.0 |

0.250 |

| 2 |

CA |

CE |

Park |

O |

24.0 |

- |

| 3 |

CO |

CE |

Historic |

NA |

0.8 |

0.727 |

| 4 |

CO |

CE |

Historic |

O |

2.9 |

- |

| 5 |

CO |

CE |

Historic |

B |

1.9 |

- |

| 6 |

GA |

EA |

Historic |

W |

72.0 |

1.440 |

| 7 |

IA |

EA |

Park |

W |

10.0 |

3.000 |

| 8 |

ID |

CE |

Historic |

NA |

0.2 |

0.003 |

| 9 |

MD |

CE |

Historic |

S |

3.2 |

0.527 |

| 10 |

ME |

CE |

Historic |

I |

1.1 |

0.038 |

| 11 |

ME |

CE |

Historic |

I |

2.3 |

0.141 |

| 12 |

ME |

CE |

Historic |

O |

0.1 |

0.004 |

| 13 |

MN |

EA |

Historic |

NA |

6.2 |

8.500 |

| |

MT |

CE |

Wildlife Refuge |

O |

1.0 |

2.000 |

| 14 |

NH |

CE |

Historic |

S |

3.2 |

0.019 |

| 15 |

NH |

CE |

Hist. and Rec. |

W |

1.2 |

0.133 |

| 16 |

NY |

CE |

Park |

I |

2.3 |

0.002 |

| 17 |

OH |

CE |

Historic |

TE |

0.6 |

- |

| 18 |

OK |

EIS |

Park |

W |

23.0 |

0.900 |

| |

RI |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| 19 |

TN |

CE |

Historic |

I |

0.5 |

0.124 |

| 20 |

TX |

CE |

Historic |

O |

0.5 |

2.275 |

| 21 |

TX |

CE |

Historic |

B |

0.2 |

0.030 |

| 22 |

TX |

CE |

Historic |

TE |

1.9 |

- |

| 23 |

VA |

CE |

Historic |

O |

3.6 |

10.780 |

| 24 |

WA |

CE |

Historic |

W |

2.7 |

0.006 |

| 25 |

WY |

CE |

Park |

O |

0.1 |

0.125 |

*B—Bridge; I—Intersection/Interchange; NA—New Alignment; O—Other; S—Safety TE—Transportation Enhancement; W—Widening

**Data from the project selected in Montana are not included in the study due to incomplete information resulting from a medical issue with the appropriate interviewee. Data for Rhode Island is listed in this table as N/A because it was interviewed as a State with no de minimis impact determinations.

^ Sizes of de minimis use with “—” values represent acreages that were unreported.

Interview Strategy

For each of the projects selected, DOT attempted to conduct interviews with at least 3 stakeholder groups that have a regulatory role in the Section 4(f) process:

- One with the State's FHWA Division Office or relevant FTA Regional Office staff

- One with the State's DOT staff or relevant transit agency staff

- One with the official with jurisdiction over the Section 4(f) property, i.e. the SHPO or THPO or the park, recreation area, and/or wildlife and waterfowl refuge official

The FHWA and FTA headquarters staff identified appropriate points of contact to interview at the FHWA Division and FTA Regional offices. Those interviewees, in turn, helped identify State DOT, transit agency, and officials with Section 4(f) jurisdiction contacts with whom additional interviews were scheduled. The DOT study team provided an interview guide (Appendix F) to all interviewees in advance of the discussions. The provision of the interview guide ensured that the respondents would understand the context for the interviews, and would have sufficient time to identify relevant staff and gather appropriate information. The interview guide also provided a measure of standardization across interviews, enabling the collection of comparable information.

In its review of the study plan and methodology, TRB recommended that an effort be made to collect quantitative data and combine it with consistent qualitative evidence to provide a weight of evidence sufficient for drawing sound conclusions. To do so, DOT provided transportation agency interviewees with a pre-interview questionnaire (Appendix F) prior to the interviews, in addition to the interview guide. Respondents were asked to return the completed questionnaire in advance of the interviews. The questionnaire was designed to complement the open-ended nature of the interview questions. It included close-ended, structured questions to produce quantifiable information that could be measured and compared across transportation agencies. (Results are reported in the sections that follow.)

The pre-interview questionnaire was sent to transportation agency interviewees in order to identify whether the agency collected Section 4(f) data, and if so, what these data were.7 The pre-interview surveys were not provided to the officials with jurisdiction because the study team assumed that, since Section 4(f) is a DOT regulation, the resource officials likely would not have been tracking data pertaining to Section 4(f) evaluations.

In total, 51 interviews with stakeholders from 20 States were conducted between September 23, 2008, and December 5, 2008. Completed interviews involved:

Transportation Agencies

- 18 FHWA Division Offices

- 1 FTA Regional Office

- 18 State DOTs

- 1 transit agency

Officials with Jurisdiction

- 10 SHPOs

- 5 officials with jurisdiction over park, recreation areas, or wildlife and waterfowl refuges

Four officials with jurisdiction (one SHPO and three officials with jurisdiction over park, recreation areas, or wildlife and waterfowl refuges) did not respond to repeated requests for an interview. In total, 82 individuals—corresponding to a response rate of 91 percent—were interviewed (between one and five people in each agency participated in the interviews). Ninety percent of the interviewees reported having experience with Section 4(f) before and after the passage of SAFETEA-LU.

Each interview was conducted via conference call and lasted between 45 and 90 minutes. The structured interviews followed the guide provided to interviewees, but also allowed for additional discussions. The discussions were conversational in nature so interviewees could provide additional insights into the implementation of the de minimis impact provision. Interviewees were also informed that no comments would be directly attributed to them in the study findings.

The study team sought additional input from key national organizations with an interest in Section 4(f) policy. Their input was collected through individual telephone interviews with staff from the ACHP and the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers. These interviews were not related to the specific projects included in the study sample, but instead were designed to collect feedback on the national policy implications of the de minimis impact provision. Two other national organizations, the National Recreation and Park Association and National Trust for Historic Preservation, did not respond to requests for interviews.

To supplement the information gathered via telephone, site visits were initially planned. The purpose of site visits was to further evaluate the post-construction effectiveness of impact mitigation and avoidance commitments adopted as part of the de minimis impact provision. However, the discussions with stakeholders led to the discovery that many of the projects processed with de minimis impacts had not actually completed the construction phase yet. Additionally, several interviewees were queried as to whether a site visit to their transportation project would offer supplementary information that could not be collected via telephone interview. The interviewees who were asked this question indicated that since their de minimis impact projects were such minor projects, usually only involving very small right-of-way acquisitions and no impact mitigation, site visits would not provide any more value than the information that was provided during the interviews. As a result, DOT determined that site visits would not add further value to the Phase I evaluation.

Study Data Quality and Research Limitations

As part of an assessment of the quality of the data utilized for this evaluation analysis, the following limitations in conducting the study and responses to those limitations are disclosed:

- The FHWA and FTA have requested and relied on their field offices to self report complete and accurate information on de minimis impact determinations. In some cases, the data are incomplete and/or reported to varying degrees of accuracy and detail.

- Inaccuracies in the information reported in the de minimis impact determinations inventory were discovered. Once errors were recognized, the data analysis team made adjustments to what information was included in the sample subject to analysis. It became apparent that two of the States initially identified as not having made any de minimis impact determinations prior to March 21, 2008, had actually done so. Although these States were initially included in the study sample, they were subsequently removed because they no longer met the criteria for which they were selected. One additional State with no de minimis impact determinations was identified and interviewed. Therefore, the final interview sample included fewer States with no de minimis impact determinations than originally intended.

- The 23 projects included in the original sample were based on the assumption that the projects had completed construction. The intent of including all projects that had completed construction in the analysis was to minimize opinions and information about project outcomes, especially information on the post-construction effectiveness of impact mitigation and avoidance commitments. Site visits were then planned to supplement project details gathered during interviews. However, stakeholder interviews revealed that a number of projects listed in the inventory as having completed construction had not, in fact, completed the construction phase. Additionally, of the projects that had completed construction, the interviewees noted that site visits were not warranted because the projects and their potential impacts were so minor. As a result, the DOT determined that site visits during Phase I would not provide additional information beyond that which was derived from the interviews.

- Most State DOTs and transit agencies do not collect or track time and cost data specific to the Section 4(f) process. As a result, statistical comparisons of resource expenditures between projects pre- and post-SAFETEA-LU were not feasible. The study findings regarding time and cost efficiencies associated with the de minimis impact provision are based on estimates and qualitative information from interviews.

- Given the qualitative nature of some of the interview questions, not all information collected during the interviews was easily verifiable. Therefore, characterizations and descriptions of outcomes of the de minimis impact process that were obtained through interviews were viewed to be individual perceptions that may not necessarily indicate views of the entire population.

- For each of the projects selected, attempts were made to conduct at least three interviews with the stakeholders that have a regulatory role in the Section 4(f) process (FHWA/FTA staff, State DOT or transit agency transportation officials, and the official with jurisdiction over the Section 4(f) resource). Four officials with jurisdiction over Section 4(f) property (one SHPO and three park and recreation officials) did not respond to interview requests. At least three attempts (by telephone and e-mail) were made to contact these officials before they were considered “nonresponsive.”

- Although equally targeted, there is an imbalance in the ratio of officials with jurisdiction to transportation officials interviewed. This imbalance is the result of more transportation stakeholders for each project, because one State DOT or transit agency and one FHWA Division Office or FTA Regional Office are always involved, whereas there is usually only one Section 4(f) property official with jurisdiction.

De Minimis Impact Determinations Inventory

The SAFETEA-LU Section 6009(c) requires the Secretary of Transportation to prepare a report that evaluated the new provisions in that section of law. The law requires that information on the number of projects with impacts that are considered de minimis, including information on the location, size, and cost of the projects be collected. Since 2005, FHWA and FTA has collected these data from their field offices. The data are compiled and saved in a spreadsheet (hereafter referred to as the “inventory”). The inventory includes information on project cost and size, class of action, type of Section 4(f) resource(s) impacted, nature of the de minimis impact determination and any associated mitigation, date of the Section 4(f) de minimis impact determination, and construction start and end dates.

An analysis of data in the inventory shows that since SAFETEA-LU was adopted, the number of projects with a de minimis impact determination per year for both highway and transit projects have followed an upward trend. In 2005, nationwide there was an average of three projects with de minimis impact determinations per month. During 2008, the last year for which data for all months are currently available, the average per month was up to 19.8. As of April 2009 — the date for which Figures 1-4 correspond — de minimis impact determinations had been made for 366 projects. Of these projects, 344 were highway projects (occurring in 44 States) and 22 were transit projects (occurring in 9 States). Five States along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico have had no de minimis impact determinations. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of projects with de minimis impact determinations by State.

Figure 1. Total Reported Projects with De Minimis Impact Determinations by State, FHWA and FTA (as of April 2009)

*Delaware, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia had no de minimis impact determinations.

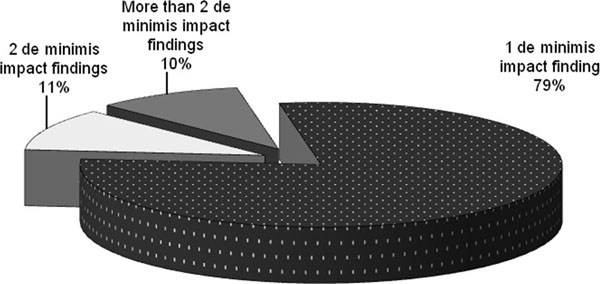

Two-hundred ninety of the 366 projects (79 percent) had a single de minimis impact determination.8 Forty projects (11 percent) had two de minimis impact determinations, while 36 projects (10 percent) had more than 2 determinations (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of De Minimis Impact Determinations per Transportation Project Type (as of April 2009)

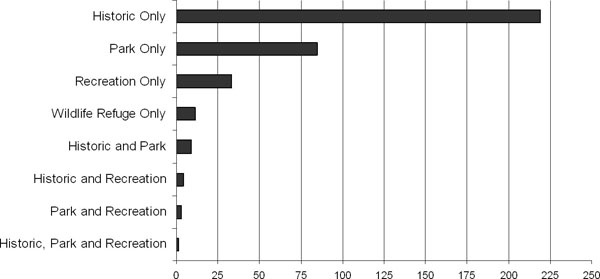

Approximately 60 percent (219) of the projects with de minimis impact determinations have been for historic property resources, 23 percent (85) for parks, 9 percent (33) for recreation areas, and 3 percent (9) for wildlife and waterfowl refuges. Approximately 2 percent (9) of the projects with de minimis impact determinations have been made on projects related to both historic properties and a park, 1 percent (4) for historic properties and recreation areas, less than 1 percent (3) for park and recreation area, and less than ½ percent (1) for historic properties, park, and recreation area. Figure 3 illustrates these data.

Figure 3. Projects with De Minimis Impact Determinations by Resource Type (as of April 2009)

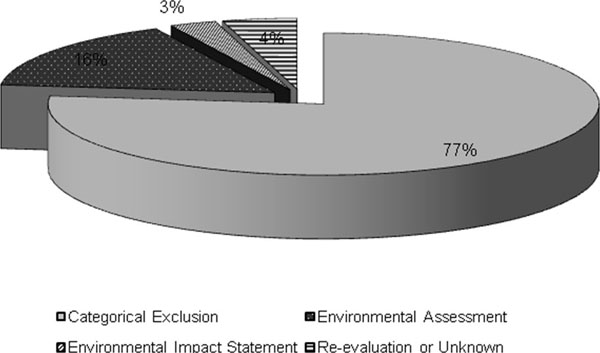

Two-hundred eighty one (77 percent) de minimis impact determinations have been made on projects with CEs. The EAs account for 16 percent (59) of projects with de minimis impact determinations, while the remainder of the determinations (7 percent; 26 projects) occurred on projects with EISs or re-evaluations or unknown environmental review documents (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Share of De Minimis Impact Determinations by NEPA Class of Action (as of April 2009)

When separated by historic and non-historic properties, the class of action distribution for projects with de minimis impact determinations is proportionately similar. Table 3 illustrates these data and provides a breakdown of cost and land area by the type of Section 4(f) resource involved, as well as between highway and transit projects.

Table 3. Class of Action, Cost, and Size of Projects with De Minimis Use Impact Determinations by Property Type (as of April 2009)

| |

HIGHWAY PROJECTS |

TRANSIT PROJECTS |

| Non-Historic |

Historic |

Both Historic

and Non-Historic |

Non-Historic |

Historic |

| Class of Action |

CE |

89 |

161 |

16 |

4 |

11 |

| EA |

22 |

31 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

| EIS |

3 |

6 |

— |

1 |

— |

| Re-evaluation or Unknown |

6 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

| Cost |

Average |

$28,052,785 |

$380,761 |

$7,587,485 |

$276,019,173 |

$26,167,222 |

| Median |

$4,950,000 |

$1,779,964 |

$3,800,000 |

$19,295,866 |

$3,100,000 |

| Minimum |

$84,000 |

$55,000 |

$165,000 |

$400,000 |

$405,000 |

| Maximum |

$450,000,000 |

$200,000,000 |

$33,500,000 |

$700,000,000 |

$130,000,000 |

De Minimis

Use Size (acres) |

Average |

0.98 |

1.24 |

0.94 |

0.0413 |

0.3826 |

| Minimum |

0.0002 |

0.0001 |

0.02 |

0 |

0 |

| Maximum |

6.50 |

38.00 |

4.00 |

0.25 |

5.7 |

| |

Highway Project Cost |

Transit Project Cost |

| Average |

Maximum |

Minimum |

Average |

Maximum |

Minimum |

| Class of Action |

CE |

$6,110,180 |

$66,900,000 |

$55,000 |

$1,843,571 |

$3,700,000 |

$400,000 |

| EA |

$41,412,663 |

$200,000,000 |

$136,000 |

$61,100,000 |

$130,000,000 |

$19,300,000 |

| EIS |

$154,152,130 |

$660,000,000 |

$1,101,301 |

$473,000,000 |

$700,000,000 |

$59,000,000 |

| Re-evaluation or Unknown |

$142,398,063 |

$700,000,000 |

$13,500,000 |

— |

— |

— |

The total project cost for highway projects that had at least one de minimis impact determination ranged from $55,000 to $450,000,000. The median cost for highway projects involving non-historic property resources was $4,950,000; for highway projects involving historic property resources it was approximately $1,780,000; and for highway projects involving both historic and non-historic resources it was $3,800,000. The total project costs for transit projects that had at least one de minimis impact determination ranged from $400,000 to $700,000,000. The median cost for transit projects involving non-historic property resources was approximately $19,300,000 and for transit projects involving historic property resources it was $3,100,000.

Road widening and bridge rehabilitation/replacement projects account for most of the highway projects that have had de minimis impact determinations (each 75 or 22 percent). Projects classified as “Other” make up the next largest group of projects with de minimis impact determinations (60 or 17 percent). See Table 4.

Table 4. De Minimis Impact Determinations by Highway Project Type (as of April 2009)

| Project Type |

Number |

Percent |

Average Cost |

Average Project

Length |

| Widening |

75 |

21.7% |

$31,894,273 |

5.40 miles |

| Bridge |

75 |

21.7% |

$21,965,072 |

0.99 miles |

| Other |

60 |

17.4% |

$20,029,420 |

2.27 miles |

| Intersection/Interchange |

46 |

13.3% |

$30,519,352 |

1.15 miles |

| Resurfacing/Rehabilitation |

22 |

6.4% |

$9,993,524 |

3.53 miles |

| Transportation Enhancement |

26 |

7.5% |

$3,591,422 |

1.39 miles |

| New Alignment |

20 |

5.8% |

$24,330,898 |

2.14 miles |

| Safety Improvements |

20 |

5.8% |

$3,334,468 |

2.63 miles |

For the 22 transit projects, facility construction or rehabilitation and expansion projects account for the majority of the projects that have had de minimis impact determinations. These type of projects included transit station modifications, transit stop construction, and railroad siding extensions and bridge rehabilitation projects.

The size of the land area of the de minimis impact use for projects in the inventory has ranged from less than one hundredth of an acre to 38 acres. The average size of the de minimis impact use is 1.13 acres. The median is 0.3 acres.

Study Findings

The following section provides the initial results from the implementation of the de minimis impact provision in three areas: (1) Efficiencies resulting from the de minimis impact provisions, including findings on the time and cost impacts of utilizing the de minimis impact provision; (2) Post-construction effectiveness of impact mitigation and avoidance commitments associated with the de minimis impact determinations, which includes findings on the impact outcomes on Section 4(f) resources and transportation project outcomes; and (3) Institutional factors associated with implementation of the de minimis impact provision.

Efficiencies Resulting From the De Minimis Impact Provisions

How do stakeholders define “efficiency” in the context of the de minimis impact provision?

When asked how they would define the term “efficiency” in the context of the de minimis impact provision, most interviewees offered a definition in terms of the time, cost, and the level of effort required to prepare Section 4(f) documentation and obtain FHWA/FTA approval. This definition of efficiency was consistent across the three stakeholder groups interviewed (FHWA/FTA, State and transit transportation agencies, and the officials with jurisdiction over the Section 4(f) resources).

Additional definitions included:

- Having the appropriate analysis done correctly the first time.

- Knowing what information you need and being able to get it quickly, and document your decisions quickly.

- Being able to get a project out to construction in a timely way if everything has been considered and is sensitive to the resource.

For the purposes of this evaluation, “efficiency” is thus characterized in terms of the time and cost savings realized when making a de minimis impact determination versus conducting and documenting alternative Section 4(f) processing methods (i.e. programmatic Section 4(f) evaluations and individual Section 4(f) evaluations).

Time Implications

Do transportation agencies collect data regarding the time involved in completing the Section 4(f) process?

A pre-interview questionnaire was sent to the transportation agency interviewees (FHWA, FTA, transit agencies, and State DOT staff) in order to identify whether the agency collected Section 4(f) data. Of the 42 Federal and State and transit transportation officials surveyed, 34 (81 percent) reported that they did not collect information on the time associated with completing the Section 4(f) process prior to the passage of SAFETEA-LU. Similarly, 30 (71 percent) of transportation officials surveyed reported that since the passage of SAFETEA-LU they have not collected data regarding Section 4(f) processing times. During the interviews, States that had indicated in the survey that they did collect data on processing times clarified that they do so only for the overall NEPA process and not specifically for the Section 4(f) process. Several transportation officials reported that they have not encountered the need to disaggregate the Section 4(f) and NEPA timelines.

The only Section 4(f) related data that transportation agencies consistently collect are data explicitly requested by FHWA and FTA for the de minimis impact determinations inventory. Since 2005, FHWA and FTA have collected information from their respective division and regional offices on the number of projects with de minimis impact determinations. Since no transportation agencies have collected information on the time it takes to complete Section 4(f) process, no quantitative information is available to report. However, the interviews gathered information on transportation agency qualitative perceptions of time savings.

Has the de minimis impact provision reduced the amount of time associated with completing the Section 4(f) process?9

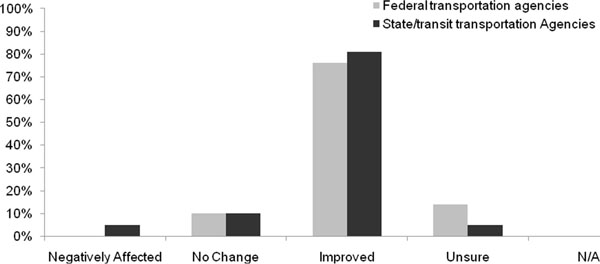

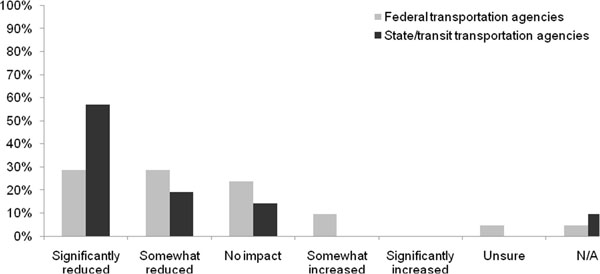

Because transportation officials have not collected data regarding the duration of the Section 4(f) process, it is not possible to quantify definitively any time savings associated with the de minimis impact provision. However, 33 (79 percent) of the transportation officials surveyed, i.e. Federal, State and transit agencies, reported that the de minimis impact provision has improved the timeliness for completing the Section 4(f) process (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Effect of the De Minimis Impact Provision on the Timeliness of Completing the Section 4(f) Requirements

According to those surveyed, the reduction in the time involved with completing the Section 4(f) process has not necessarily equated to time savings within the overall environmental review process. That is because Section 4(f) is just one of many aspects contributing to the length of time necessary to complete the NEPA process.

One State DOT reported that the de minimis impact provision has increased the time associated with completing the Section 4(f) process. This situation is unusual because the State DOT and the FHWA Division Office have a unique Section 4(f) Programmatic Agreement (PA) that allows the State to administratively determine the applicability of the nationwide programmatic Section 4(f) evaluations to projects processed under a CE. When this State DOT approves a programmatic Section 4(f) evaluation, the agency sends the evaluation to its FHWA Division Office and proceeds with the project without additional paperwork if FHWA, which retains its oversight and monitoring role, does not object within 15 days from receipt of the evaluation. The Section 4(f) PA does not apply to de minimis projects, and therefore, that State DOT has to send its de minimis documentation to the FHWA Division Office and then wait to receive formal approval before proceeding. The approval process typically takes longer than 15 days, resulting in the de minimis impact process having a longer timeframe than programmatic Section 4(f) evaluations.

How have the various aspects of the de minimis impact provision affected the timeliness for completing the Section 4(f) process?

Transportation officials were asked to rate how the following factors of the de minimis impact provision have affected the time associated with completing the Section 4(f) process:

- Elimination of the requirement to coordinate with and obtain comments from DOI

- Elimination of the FHWA/FTA legal sufficiency review process

- Elimination of the requirement to design and evaluate alternatives

- Addition of the public comment and review requirements (for parks, recreation areas, and refuges)

- Relying on a Section 106 determination to reach a 4(f) determination (for historic properties)

Elimination of the requirement to coordinate with and obtain comments from the DOI

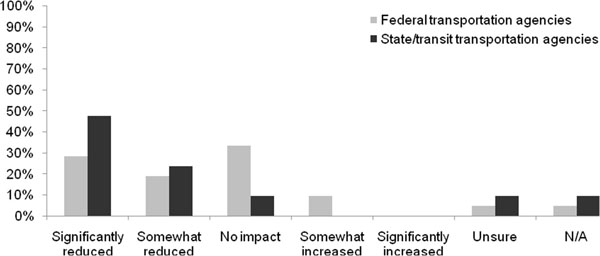

Eighteen (43 percent) of the transportation agencies surveyed reported that the elimination of the requirement to coordinate with and obtain comments from the DOI significantly reduced the time associated with completing the Section 4(f) process (see Figure 6). However, interviewees noted that a programmatic Section 4(f) evaluation10 does not require coordination and review by the DOI. Therefore, any savings attributed to this factor would only occur if, in the absence of the de minimis impact provision, the project would have been processed through an individual Section 4(f) evaluation. Of the 25 projects analyzed, 19 would have been processed using a programmatic Section 4(f) evaluation in the absence of the de minimis impact provision. The remaining projects include two that would have been processed using an individual evaluation, two projects that would have avoided the Section 4(f) property, one project that would not have been built, and one that would have qualified as a temporary occupancy under Section 4(f) regulations and thus exempt from Section 4(f) requirements.

Figure 6. Effect of the Elimination of the Requirement to Coordinate With and Obtain Comments from DOI on the Time Associated with Completing the Section 4(f) Process

Elimination of the FHWA/FTA legal sufficiency review process

Sixteen transportation agencies (38 percent), which include Federal, State and transit agencies, reported that the elimination of the FHWA/FTA legal sufficiency review process significantly reduced the process (see Figure 7). Similar to the DOI comment requirement, a programmatic Section 4(f) evaluation does not require FHWA/FTA legal sufficiency review. Therefore, any savings attributed to this factor would only occur if, in the absence of the de minimis impact provision, the project would have been processed through an individual Section 4(f) evaluation.

Figure 7. Effect of the Elimination of the FHWA/FTA Legal Sufficiency Review Process on the Time Associated with Completing the Section 4(f) Process

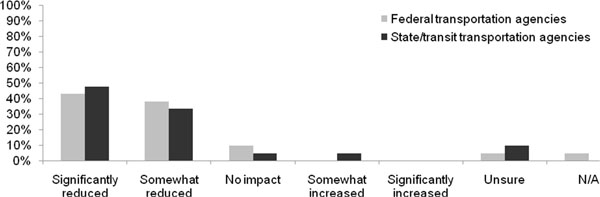

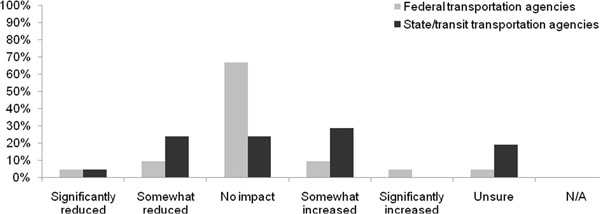

Elimination of the requirement to design and evaluate alternatives

A primary difference between processing Section 4(f) through a de minimis impact determination versus a programmatic evaluation or individual Section 4(f) evaluation is the elimination of the requirement to design (or develop) and evaluate alternatives to using the Section 4(f) resource. Of the Federal and State/local transportation agencies surveyed, 19 (45 percent) reported that this factor significantly reduced the time associated with completing the Section 4(f) process (see Figure 8). The actual time savings gained from being able to make a de minimis impact determination varies according to the level of difficulty involved in analyzing avoidance alternatives, as well as the workload of the design engineers. Interviewees estimated that the time savings from not having to develop or evaluate alternatives ranged from as little as a couple of hours to as much as 6 months (although the timeframes were based on estimates and not independently verifiable data). Transportation officials who selected “No impact on time” for the option “Elimination of the requirement to design and evaluate alternatives” clarified that even though they are not required to document the evaluation of alternatives, they still conduct an alternatives analysis for many projects in order to assess what the project's effects are prior to making the de minimis impact determination, or to consider other resources or issues.

Many of the transportation officials interviewed stated that the elimination of the requirement to design and evaluate alternatives has not changed the outcome of transportation projects in general, but has enabled their agencies to reach the outcome (i.e. the final project design) in a more streamlined manner. For instance, prior to the de minimis impact provision, when evaluating alternatives under either the programmatic evaluation or the individual evaluation processes, a transportation agency would typically determine that modifying a project to avoid a minor impact to a Section 4(f) resource was not prudent and feasible due to reasons such as increased environmental impacts to non-Section 4(f) properties. Most interviewees found that the removal of the alternative analysis process from projects that have minimal impacts on Section 4(f) resources has streamlined Section 4(f) compliance without compromising the original intent of Section 4(f).

Figure 8. Effect of the Elimination of the Requirement to Design and Evaluate Alternatives on the Time Associated with Completing the Section 4(f) Process